Climber Posture

Many climbers seem to be haunted by the idea that they need to correct their posture.

They believe that correcting their posture would help relieve pain or prevent injury.

Can you relate?

I used to believe this was true myself until only recently.

Several years ago I wrote a popular article titled “Climber Posture” that discussed posture and it’s relevance to climbers.

Turns out I was wrong about a lot of things in that article.

In the last several years since then, I have learned a lot more about pain science, posture, injury, and what the current scientific literature says about these topics.

In this post, I will discuss the current understanding of posture as it relates to pain and injury, and I will back it up with some science.

WHAT IS NORMAL POSTURE?

Posture can be defined as the position in which you hold your body while standing or sitting. It usually refers to a static position.

Many people have an idea in their head about what ideal posture is. A tall, erect posture with shoulders back and a straight spine.

The reality is...

We don’t seem to have a consensus for “normal” for posture in the scientific literature.

There is a lot of variance within the asymptomatic population so it’s hard to say which postures are bad and which are good.

There are people with “poor” posture that have NO pain and there are people with “good” posture that DO have pain and vice versa.

Check out this video about posture from Greg Lehman: Perfect posture doesn’t exist.

WHAT IS POOR POSTURE?

If we can’t decide what “normal” is then how do we know what “bad” is?

The truth is...we don’t.

Regardless of that, there is still information out there attempting to describe what “bad posture” is. My old blog post is one example.

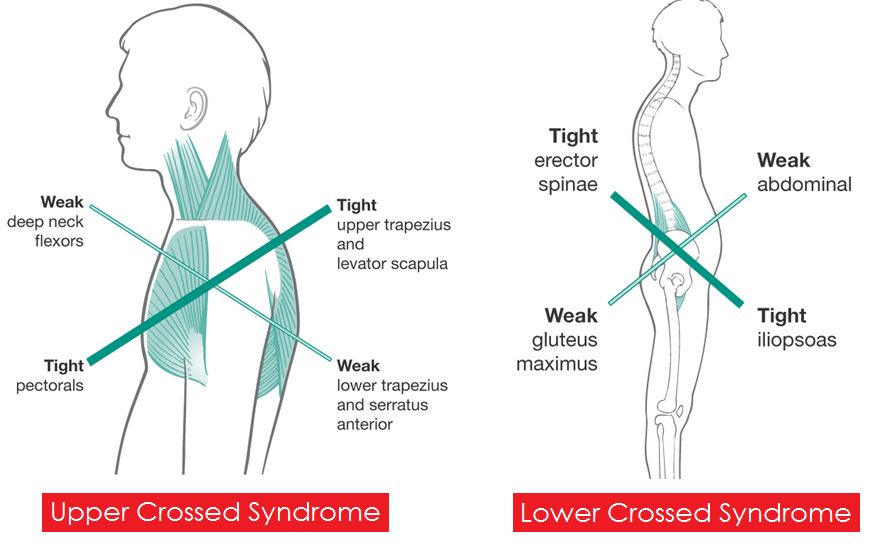

The most commonly used example of “poor posture” is something called “Upper Crossed Syndrome.” UCS was named by Czech doctor and researcher, Vladimir Janda.

UCS describes the classic forward head posture and rounded upper back and forward shoulders.

This is essentially what “climber posture” is defined as.

The causes of UCS and “poor” posture, in general, are commonly thought to be muscle imbalances that cause alignment and asymmetry problems.

What’s typically described is short, tight muscles pulling on longer weak ones causing changes in the position of your upper back, neck and shoulder blades.

The consequences of these changes are often said to be an increased chance of pain and injury.

HERE’S THE PROBLEM…

While it may sound like a logical idea (it did to me a few years ago!), the problem is that there is no good scientific evidence to support ideas like “Climber Posture” or UCS.

There is actually a lot of research showing that posture, muscular imbalances, and asymmetries don’t seem to correlate with injury or pain. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Even if they did, we have evidence that when assessing posture and asymmetries, practitioners have a very hard time agreeing on what exactly is wrong. [7, 8, 9, 10, 11]

Inter-rater reliability is very low for these tests and assessments meaning, if you go to 5 different people to have your posture assessed, you’ll likely get 5 different takes on what’s wrong.

Doesn’t that seem problematic?

CAN WE “CORRECT” POSTURE?

Even if we could define good vs bad posture and reliably identify it, can we correct it?

Your posture is likely an adaptation to deeply ingrained postural habits that have been developed over years and decades as well as to the demands of regular climbing practice.

There doesn’t seem to be a whole lot of reliable data showing that we can effectively change posture via commonly prescribed stretching and strengthening exercises.

In fact, there is some data to the contrary. [12]

“CLIMBER POSTURE” MIGHT BE NORMAL

Even with the limited research we have within our sport of climbing, it seems like muscle imbalances and “climber posture” may just be an adaptation to the training demands of climbing [13, 14, 15].

In 2014 a small, climbing specific study was done to assess the posture of rock climbers and the factors contributing to changing the shape of curvature of the spine in the sagittal plane.

The study group consisted of 58 male subjects with a mean age of 24. They were divided into 2 groups.

Group 1: men who had been climbing for at least 2 years (27 subjects).

Group 2: men who did not practice the sport (31 subjects).

Subjects with a history of either previous spine injury or diagnosed postural defect or those who were practicing other sports at least 6 hours a week, were excluded from the study.

The climbers' skill level varies from beginners (48%) to professionals (52%).

The study showed a significant relationship between the level of climbing, and the shape of the thoracic curvature. The harder the subjects climbed the more of a thoracic curve they had.

There seemed to be a strong correlation between the duration and intensity of training and the degree of thoracic curvature.

The study concluded that the practice of rock climbing seemed to contribute to changes in posture in the form of increased thoracic kyphosis or “climber’s back” as it’s termed in the study.

Given this information, it’s likely that the development of “climber’s back” aka “climber posture” is simply an adaption to the imposed demands of climbing.

Postural adaptations due to the demands of sport have been confirmed in studies of other sports as well. [16, 17, 18]

POSTURE DOES NOT CONTRIBUTE TO SHOULDER PAIN

Shoulder injuries account for 17% of all climbing injuries according to a 2018 research review [19].

These injuries are often blamed on “climber posture” which consists of a rounded upper back (thoracic kyphosis) but according to the research, thoracic kyphosis does not seem to be an important contributor to the development of shoulder pain [20].

SHOULD YOU WORRY ABOUT YOUR POSTURE?

If posture doesn’t correlate well to pain or injury, can’t be reliably measured or “corrected,” and is just an adaptation to imposed demand...should you be worrying about it as much as you do?

Probably not.

Worrying about posture probably causes more harm than good.

If a therapist tells you that you have a postural dysfunction, that has the potential to cause harm via the nocebo effect (the opposite of a placebo effect).

You can start experiencing pain that is caused by the simple belief that something is wrong.

Your expectations and beliefs are important. For example, this 2011 study explored how expectations can change the effects of a powerful drug. [21]

In the study, researchers applied a hot laser to the participants and recorded the average pain level at 66/100.

The researchers then hooked up the participants to an IV and they were told it was just saline solution. Without their knowledge, the participants were actually being given a very powerful opioid called Remifentanil. Remifentanil is a pain-killer 250x more powerful than morphine.

The researchers reapplied the laser and the participant’s pain level went down to 55/100.

Remifentanil reduced pain by an average of 11 points without the participants even knowing they were on it.

In the next part of the experiment, the participants were told they were going to be given a powerful pain-killer through the IV.

In reality, the researchers didn’t change anything because the participants were already receiving the drug. The only thing that changed was the participants being made aware of the drug.

The researchers reapplied the laser and the participant's pain level went down to 39/100.

The drug became 30% more effective simply by the participants being made aware of the drug they were already receiving.

In the last part of the study, the participants were told the drug would be stopped and that they would go back to receiving just the saline solution.

The researchers actually didn’t change anything and the participants continued to receive the Remifentanil. All that changed was the subjects thinking they were being taken off the drug (negative pain expectations).

The researchers reapplied the laser and the participant's pain level went back up to 66/100. That was the original pain level without the medication!

The belief that the medication was being stopped was enough to effectively reverse the effects of the medication (nocebo effect).

This experiment shows that negative expectations can completely block the effect of an opioid 250x more powerful than morphine.

This is how powerful the mind is when it comes to pain.

If you believe slouching all day in front of the computer is bad and you expect that it will cause pain, there is a possibility that you will experience pain due to your expectation of it.

As a therapist, I believe that it can be problematic to call out unsubstantiated “postural dysfunctions.”

It can drive beliefs about general vulnerability and fragility, and often cause people to become hypervigilant about posture.

Postural hypochondriacs, if you will.

WHY DO SO MANY THERAPISTS STILL TRY TO CORRECT POSTURE?

“...structuralism is deeply embedded in our cultural consciousness, and we cling to the idea that aligned and symmetrical must be the best way to be, and we suffer in proportion to our deviations from that diagram. That equation makes intuitive sense to us, and we’re just not going to give it up easily!” -Paul Ingraham, PainScience.com

Many therapists have a bias towards structuralism and the biomedical model since we were taught this way in school and it makes logical sense.

Many are ignorant of what the current research says on the topic of pain and posture. I definitely used to have this bias having studied at a chiropractic college!

The sunk cost fallacy can also be a contributing factor here. If you invested $225k into an education that reinforces the biomedical model it can be hard to stop doing what you have been taught, spend more time and possibly money re-educating yourself and completely change the way you practice.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his job depends on not understanding it.” -Upton Sinclair

It can be hard to get therapists away from structuralism when their job is based on attempting to identify and correct dysfunctions and asymmetries and this is how they are getting paid by insurance companies.

Confirmation bias can also be a problem. If you’re looking for postural problems and asymmetries, confirmation bias says you’re likely to find them.

WHY DO YOU HAVE PAIN THEN AND WHAT CAN YOU DO ABOUT IT?

Pain is a complex topic, too large to go into detail in this post.

It is influenced by many things including tissue damage, beliefs/attitudes/expectations about pain, prior experiences, stress etc.

If you’re having pain there are a few things you can do:

Learning about how pain works.

Here are some great resources:

Why Do Muscles Feel Stiff and Tight?

Changing your positions frequently.

Pain associated with posture is usually more of something called “postural stress.” Some people are sensitive to certain postures or positions.

The best posture is the one you’re not in.

Sit up straighter, slouch, stand up, sit down, go for a walk, change the position you’re in.

Changing your attitude towards posture.

There are no “good” or “bad” postures, there are just ones you’re more sensitive to or unadapted to. Sitting or standing in certain ways is not going to cause damage.

As demonstrated earlier, negative beliefs and expectations can lead to pain.

Beliefs about pain are strongly associated with disability. The more negative your beliefs are the higher your risk of disability. [22]

MY GOAL WITH THIS POST

My goal with this post is not to prove anyone wrong or be antagonistic. My goal is to help other people be less afraid of their own bodies.

As a professional climber, I spent a lot of time dealing with injuries before going to school and during school. I was told (and strongly believed) they were due to postural problems and muscle imbalances.

I constantly felt guilty for not “fixing” my posture and I felt weak because I thought I had severe muscle imbalances.

Foam rolling, lacrosse balling and doing all of the usual PT exercises helped a little bit symptom-wise but I never got any stronger and it didn’t seem to “fix” any imbalances or postural issues I thought I had.

I was so convinced that upper back and shoulder pain I had was due to a stiff thoracic spine caused by my posture. I would spend inordinate amounts of time “mobilizing” my thoracic spine.

At first, I could barely tolerate a lacrosse ball in my back but I eventually worked up to rolling it by laying on the floor with a 45# plate on my chest or having a friend push down on me as hard as they could.

I ended up causing an injury to my upper back in my quest to unlock my thoracic mobility. In actuality, I had plenty of thoracic mobility, I just “felt tight” and it was the wrong thing to worry about.

Through further education and strength training, I was able to resolve my injuries without working on my posture or my mobility or even considering my scapular mechanics.

I see a lot of you in my sports medicine practice haunted by the same worries I had. I want to make sure that you aren’t nocebod, that you don’t feel scared of your body and broken.

I don’t want you to fall into the same traps I did.

I’d rather help you focus on the things that really matter. I’m going to be writing more about those things in upcoming blogs, so stay tuned!

WHAT’S THE TLDR?

Ideal posture doesn’t exist.

Posture doesn’t correlate well with pain or injury.

Posture can’t be reliably measured or “corrected.”

Posture in athletes may just be an adaptation to the imposed demand of sport.

If you have pain, change positions. If you don’t have pain, don’t worry about it.

Don’t be a posture hypochondriac!

Further Reading:

1.Psoas and quadratus lumborum muscle asymmetry among elite Australian Football League players. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18801772

2. Neck Posture Clusters and Their Association With Biopsychosocial Factors and Neck Pain in Australian Adolescents. https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article/96/10/1576/2870247

3. Text neck and pain in 18-21-year-old young adults. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29306972

4. Spinal curves and health: a systematic critical review of the epidemiological literature dealing with associations between sagittal spinal curves and health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19028253

5. The curve of the cervical spine: variations and significance. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8133194

6. Diagnostic accuracy of scapular physical examination tests for shoulder disorders: a systematic review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23080313

7. Agreement between physiotherapists rating scapular posture in multiple planes in patients with neck pain: Reliability study.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25749493

8. Reliability and validity of head posture assessment by observation and a four-category scale. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20627799

9. The reliability of physical examination tests for the clinical assessment of scapular dyskinesis in subjects with shoulder complaints: A systematic review. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28237770

10. Comparative study between symmetrical and asymmetrical sports by static structural analysis in adolescent athletes. http://archivosdemedicinadeldeporte.com/articulos/upload/or02_alvarez_ingles.pdf

11. How do we stand? Variations during repeated standing phases of asymptomatic subjects and low back pain patients. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021929017303135

12. Is thoracic spine posture associated with shoulder pain, range of motion and function? A systematic review https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27475532

13. Kyphosis in older women and it’s relation to back pain disability and osteopenia: the study of fractures. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8148573

14. The association between spine curvature and neck pain. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17115202

15. Strength Profiles of Shoulder Rotators in Healthy Sport Climbers and Nonclimbers https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2742463/

16. THE CHARACTERISTIC BODY POSTURE OF PEOPLE PRACTICING ROCK CLIMBING

17. Differences in humeral retroversion in dominant and nondominant sides of young baseball players. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28131683

18. Osseous adaptation and range of motion at the glenohumeral joint in professional baseball pitchers. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11798991

19. Climber's back--form and mobility of the thoracolumbar spine leading to postural adaptations in male high ability rock climbers. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18651371

19. Incidence, Diagnosis, and Management of Injury in Sport Climbing and Bouldering: A Critical Review.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30407948

20. A review of resistance exercise and posture realignment. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11710670

21. The effect of treatment expectation on drug efficacy: imaging the analgesic benefit of the opioid remifentanil. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21325618

22. The Relationship between Pain Beliefs and Physical and Mental Health Outcome Measures in Chronic Low Back Pain: Direct and Indirect Effects https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5041059/